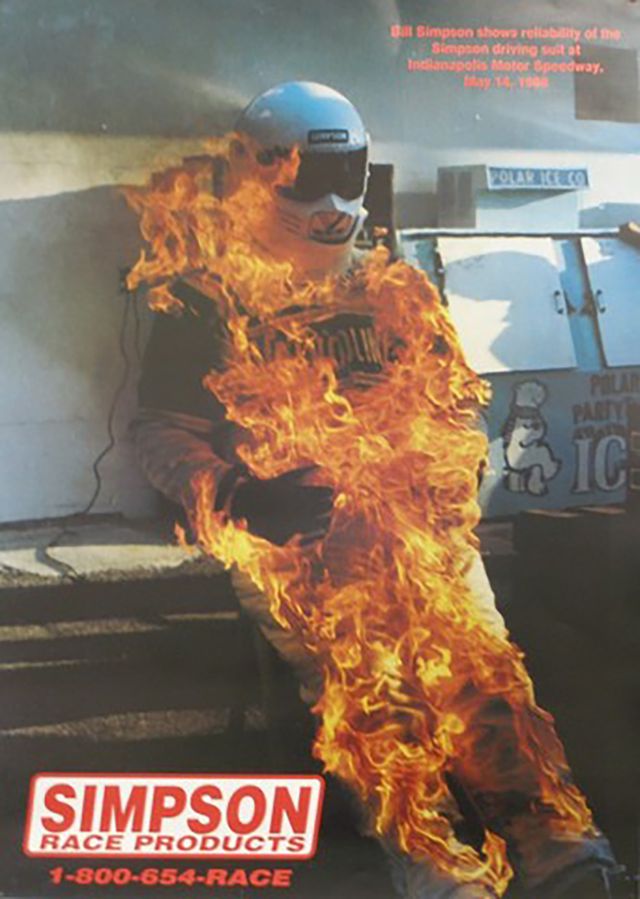

The ad that brought fame to Bill Simpson was a perfect visual depiction of the man.

Set ablaze in 1986 wearing a flameproof driver’s suit, shoes, socks, gloves, and helmet bearing the name of his motor racing equipment company, the safety pioneer, who died at the age of 79 on Monday, burned bright shades of red until the fire was extinguished.

Simpson, the human torch, sat as waves of heat furled skyward, proving the value and quality of his products in the most Simpson way imaginable. If the company’s founder was willing to willing to risk his life inside the very layers of Nomex he sold, what excuse did drivers have to go elsewhere for their safety gear?

"If you ever did anything in racing where you had to put a helmet on, seatbelts on, a fire suit, shoes, gloves, fireproof underwear, at some point he touched your life," Simpson’s friend and three-time NASCAR Cup champion Tony Stewart told Road & Track.

It was an encounter with Apollo 12 Commander Pete Conrad in the late Sixties that would trigger a massive change in the sport. The racing-mad NASA astronaut introduced Simpson to the space-age material Nomex, developed by DuPont and used in space suit construction, among other applications. It transformed driver safety. Death by fire was an all-too-familiar outcome in heavy crashes, and despite rudimentary efforts—like soaking T-shirts and pants in bathtubs filled with water and chemical agents designed to combat flames—the board-stiff garments were no match for burning gasoline and oil.

Nomex, as Simpson learned, wouldn’t offer a truly fireproof solution. But the fabric’s properties bought drivers crucial seconds of protection, often enough to climb from a car and roll on the ground to put out the fire, or to be reached by safety workers with fire extinguishers to stop the burning before it reached skin.

Although others had made prototype racing suits with Nomex before Conrad’s NASA tech transfer, Simpson was the first to grasp its wide-ranging need in motor racing and take action.

"It didn't matter what area of racing you were involved in," said Stewart, a veteran of Midwest dirt oval racing who went on to win an Indy Racing League title before NASCAR beckoned. "I mean, Simpson was always present, and the thing is, he always cared about his buddies. That's how he got into all of this. He didn't want his buddies getting hurt."

From mass-producing Nomex fire suits to fashioning the first parachutes to slow dragsters to a safe speed after tripping the timing lights, Simpson found his calling in saving lives.

"I don't know that there was anybody in the sport that was more concerned about safety," adds another dear friend of Simpson, former Indy car racer and legendary team owner Chip Ganassi. "[Others] may have more knowledge in the 'club of safety,' but they are in a club that was started by Bill Simpson."

Simpson’s mark on the sport was driven by trust. With more than 50 Indy car starts spanning from 1968 to 1977, including one at the 1974 Indy 500, Simpson cemented his own reputation as a fellow racer whose safety products performed in dire conditions. He was the foremost evangelist of his kind; large swaths of teams and drivers would come to rely on Simpson’s innovations as speeds increased at a faster rate than barrier and crash abatement technology. Racing helmets, including the iconic all-black "Darth Vader" model, became synonymous with the Simpson brand in North America and Europe as he dedicated vast amounts of money and time into reducing weight and optimizing padding materials.

Decades later, after Simpson’s company was sold, his work on advancing helmet safety continued. This time, it was in football, with a goal to reduce concussions by distilling all he’d learned in racing into a product made for the gridiron. Ganassi was his partner in the venture.

"You know, we went down one time to the NFL testing center, a place where they do all their helmet testing, in Knoxville, Tennessee," Ganassi said. "This was a few years ago, as the epidemic of football concussions was coming to light. At the time they were doing all their testing there, and the guy that ran the place was bowing when Bill walked in the door. He said, 'Man you're a hero in our business.'

"You know, the testing that they do in racing was pretty much invented by Bill Simpson, and the tests they ran there were pretty much invented by Bill, taken from what he’d done in racing. Bill went, 'Hey I got this new helmet we want to try out for football, I wanted you to test it.' We wanted to do an independent test there and the guy was just honored that Bill was there."

Stewart recalls the backlash Simpson received from the NFL and the helmet manufacturers who paid the league to have their products used by its players.

"It was the safety aspect of it, whether it was the sport in general, he was always looking at what was going on," he said. "I mean, look what he did on the football side. It was the same thing. He didn't have to get involved in that, and Lord knows they screwed him over eight ways from Sunday, the NFL did, with their bullshit deals with this company and that company, when Bill had a better product. Here’s a guy, made an investment to try to take care of not only race car drivers, but to look into other sports and try to make them safer. And because of the almighty dollar, these big football helmet companies were able to try to push him out of the sport.

"He was just trying to help, and he'd tell you, he didn't give a shit. He knew what he was doing and why he was doing it, and if the NFL was dumb enough to let [more injuries] happen, then so be it. But that's on those dumb asses. I mean, it's a shame when you got somebody that's trying to make everybody safer, and the politics and the crap that he went through on that side, that's the stuff that you hate. He saw things and he said, 'Hey, I got to find a way to make it better.'"

Beyond his contributions to the sport, Simpson was a cantankerous delight—for some.

Like the famous scene portrayed in the magazine ad, those fiery hues had been seen many times before, often by the friends and business partners who wandered back and forth across the line between love and hate in their relationships with the Californian. Few in the sport have occupied such a polarizing place as Simpson, though in many instances, long-held grudges eventually gave way to reconciliations. If he reckoned you were worth a damn—and if you survived the endless volley of curse words—being inducted into Simpson’s circle of heathens was the ultimate honor.

"He was a one-of-a-kind individual," Stewart affirmed. "I mean, there's the people that thought he was an asshole, people that didn't know him well enough to know the different sides of him. He could be an asshole one minute and an hour later be one of the nicest, most generous, caring guys you've ever seen in your life. He just never pulled any punches. If he liked you, he liked you. If he didn't like you, he didn't like you."

Stewart, with pride, is possessed by many of the same traits.

"One thing is, you always knew where you stood with him. He just was Bill Simpson and there's just not a lot of people like that," the Indiana native continued. "I mean, there's very few people that just do it their way and don't pull any punches. That's why I think we all respected him as much as we did. For what he was doing and why he was doing it from the safety side, but also, for who he was as a person.

"There's times he annoyed the shit out of me, but there were times that if he called me at four in the morning, said, 'Hey, I need you to come over here, I got to show you something,' I'd get up and get dressed and go do it in a heartbeat," Stewart said.

Ganassi was drawn to Simpson’s achievements as a self-made success.

"He was one of the most street-smart people I knew. He was nobody's fool, and literally pulled himself up in life, from being an orphan," he said. "He pulled himself up by his bootstraps, and did it all himself, and he did it his way. He didn't have any bullshit about him when it came to safety. Yeah, he was as fun-loving a guy as anybody, but when it came to safety, he was all business."

How many lives has Bill Simpson saved? Thousands? Tens of thousands? Determining the exact number is all but impossible. Measuring the man's impact on our sport is equally challenging.

"I think the word safety, in terms of motor racing, squarely rests on his shoulders," Ganassi said. "It was not just parachutes, helmets, fire suits. It was everything to do with the car and the car crashes and the g-forces and how the cars were folding up, how they were handling an impact. He was on many different plateaus of the sport. And you know, you didn't always like to hear what Bill had to say, but he didn't have any bullshit about him when it came to safety."

Stewart laments the loss of an epic character and innovator.

"You aren't going to see that again," he reckons. "I would say in my lifetime, we'll be lucky if we see somebody in motorsports that's as far ahead of everything, and that forward thinking. I mean, you look at just the safety aspect alone. It's all corporations and companies that are doing this now. It's not one man, one vision. A guy that's firsthand, at ground zero, who sees it all, feels it all, does it all and understands it all. It's not like that anymore. There just aren't people with the personality like Bill to be that assertive on their own."

In our world, Simpson became a singular word that did not require an explanation. He made products that saved us in cars, on bikes, and on pit lane. He was safety. And he was one of us.