Rope or rod? Torn between scoliosis surgeries

One’s tried and true. The other’s promising, but uncharted in the long term. Which would you choose?

Listen 14:11

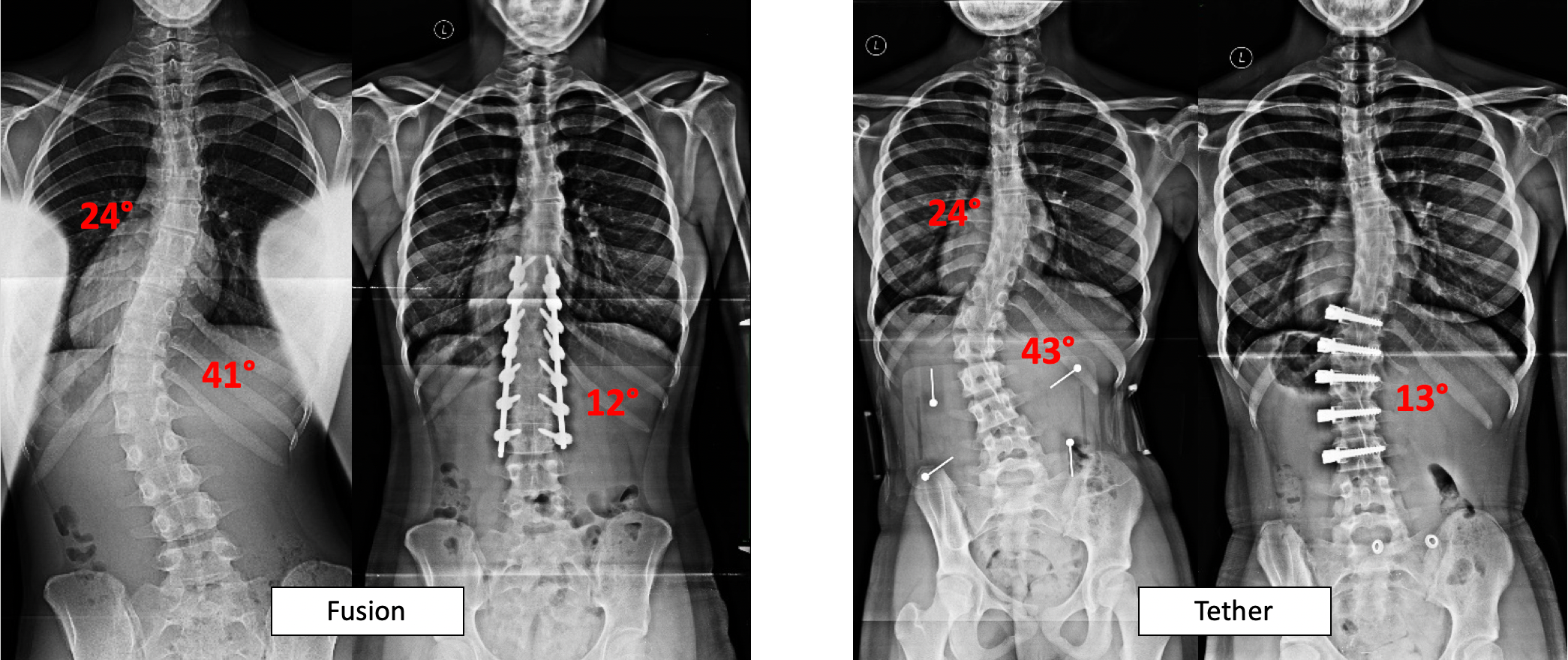

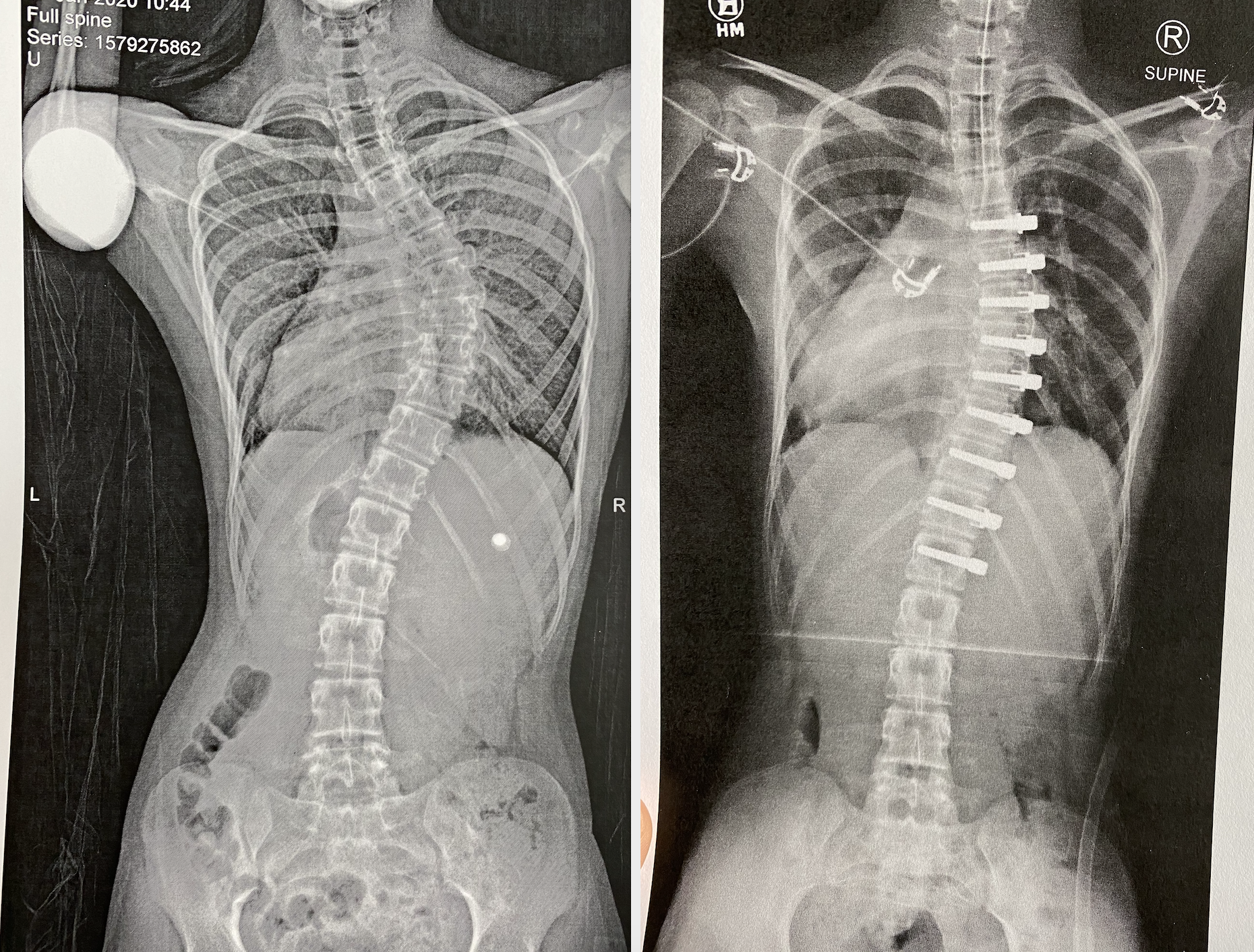

X-rays showing a spine with scoliosis before and after surgery. (Image courtesy of Shriners Hospitals for Children — Philadelphia)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher or wherever you get your podcasts.

For a long time, spinal fusion was the only surgery to treat scoliosis. Over the years, the operation has improved and become the gold standard. But now, there’s another procedure available. Though it seems to offer big advantages, its long-term outcomes are uncertain. How do you weigh one against the other? We followed one family as they made a decision.

No more back flips

Bailey Pentz, 13, has been doing gymnastics and cheerleading most of her life.

She and her family live in Parker, Pennsylvania, a town outside Pittsburgh that bills itself as “the smallest city in the United States.”

The family has hours of footage of Bailey in cheer competitions and practicing tumbling routines. In video after video, she’s trying to master one move: the back handspring. Two or three years ago, she could land several in a row.

But lately, she hasn’t been able to do a single back handspring.

“Because my back got so bad, and it hurts if I try to do it,” Bailey said.

In recent years, gymnastics and cheerleading have gotten harder and harder for Bailey. Last fall, she had to drop out of gymnastics entirely. “It’s sad and kind of stressful, that you’re trying to do it but you can’t,” she said.

What’s keeping Bailey from her gymnastics is scoliosis. She has what’s called adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, idiopathic meaning its causes are unknown. It’s the most prevalent spinal disorder in teens — as many as 5% have it.

Her mom, Beth Pentz, said Bailey’s pediatrician detected her scoliosis when she was 9 years old. “They just did that simple test that we used to do,” Beth said. “Bend over and touch your toes. And when she did, they noticed that she had a curve.”

Bailey’s curve was concerning. Over the next several years, her doctors monitored its progression. Bailey tried physical therapy, and two different braces. But she was in constant pain.

“I have back pain a lot,” Bailey said. The curve in her spine also created tension in her neck and head. She had headaches or migraines almost every day.

When you’re looking at a spine from the back, it should be a straight line, zero degrees. But in Bailey’s case, the backbone took a sharp turn to the left, 48 degrees and counting. On X-rays, you saw what looked like a backwards C in the middle of her spine.

And her curve kept getting worse. Last October, Bailey visited her doctor. “He said, ‘We’re kind of at the end of our bracing journey,’ like surgery was the next route,” Beth said.

The established option

For about 10% of teens with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, bracing and physical therapy aren’t enough. Each year, some 30,000 scoliosis surgeries are performed on teens in the U.S. When doctors recommend surgery, it usually means that, left alone, the scoliosis will continue to get worse. Eventually, it will start to crowd other organs, and affect lung function and breathing.

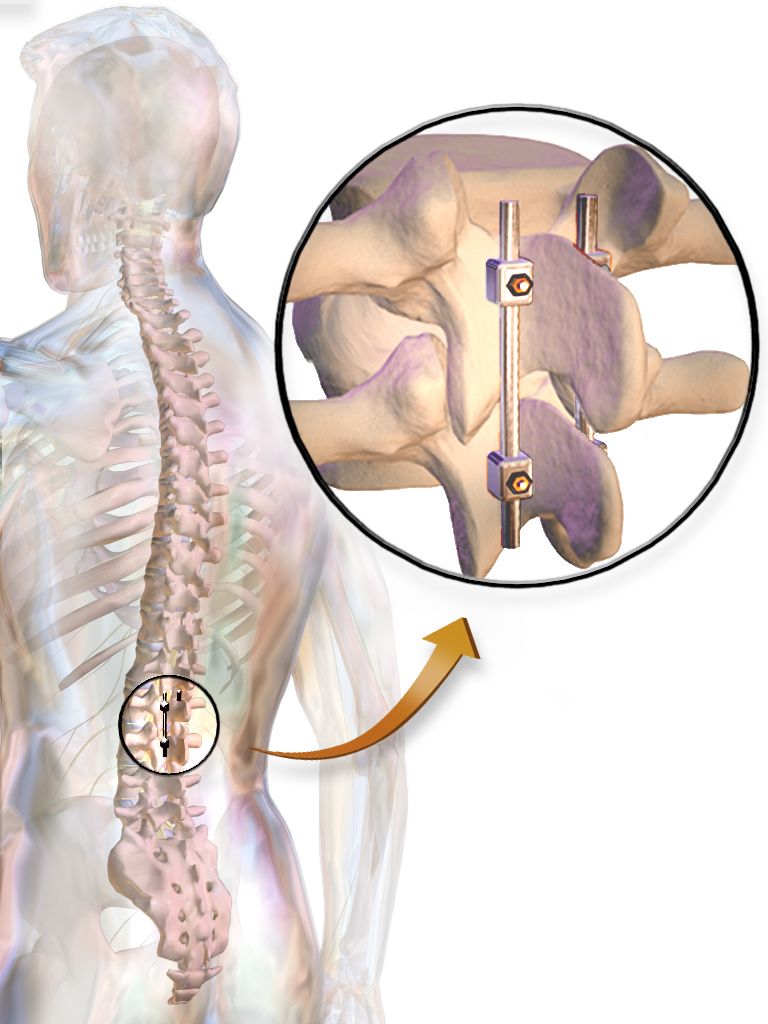

Bailey’s doctor told her she should get what’s called a posterior spinal fusion. For a long time, that was the only surgery for scoliosis.

Patrick Cahill, a spine surgeon at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, explained how a spinal fusion works. First, surgeons cut open the back — “a fairly long incision, where the muscles are dissected off of the bones of the vertebrae.”

Then surgeons install screws on the sides of each vertebra, or each bone along the affected part of the spine. Next, they feed a metal rod, about the diameter of a pencil, through the screws. It looks something like braces, for the spine. “Those are used to pull the curved spine over to a straight alignment,” Cahill said.

Then comes the fusion part. The doctors roughen up and break off bits of the vertebrae, to trick the body into thinking that it has a broken bone. In response, the body starts to grow new bone. “Then bone graft is laid on the back of the vertebrae,” Cahill said, “so that as they grow new bone, they sort of coalesce and grow into one long bone between all of the vertebrae.”

Spinal fusion has been done in this general way, with metal rods, for 60 years now. Its current form is considered the gold standard in scoliosis surgery, and it’s a big improvement from how operations have been done in the past.

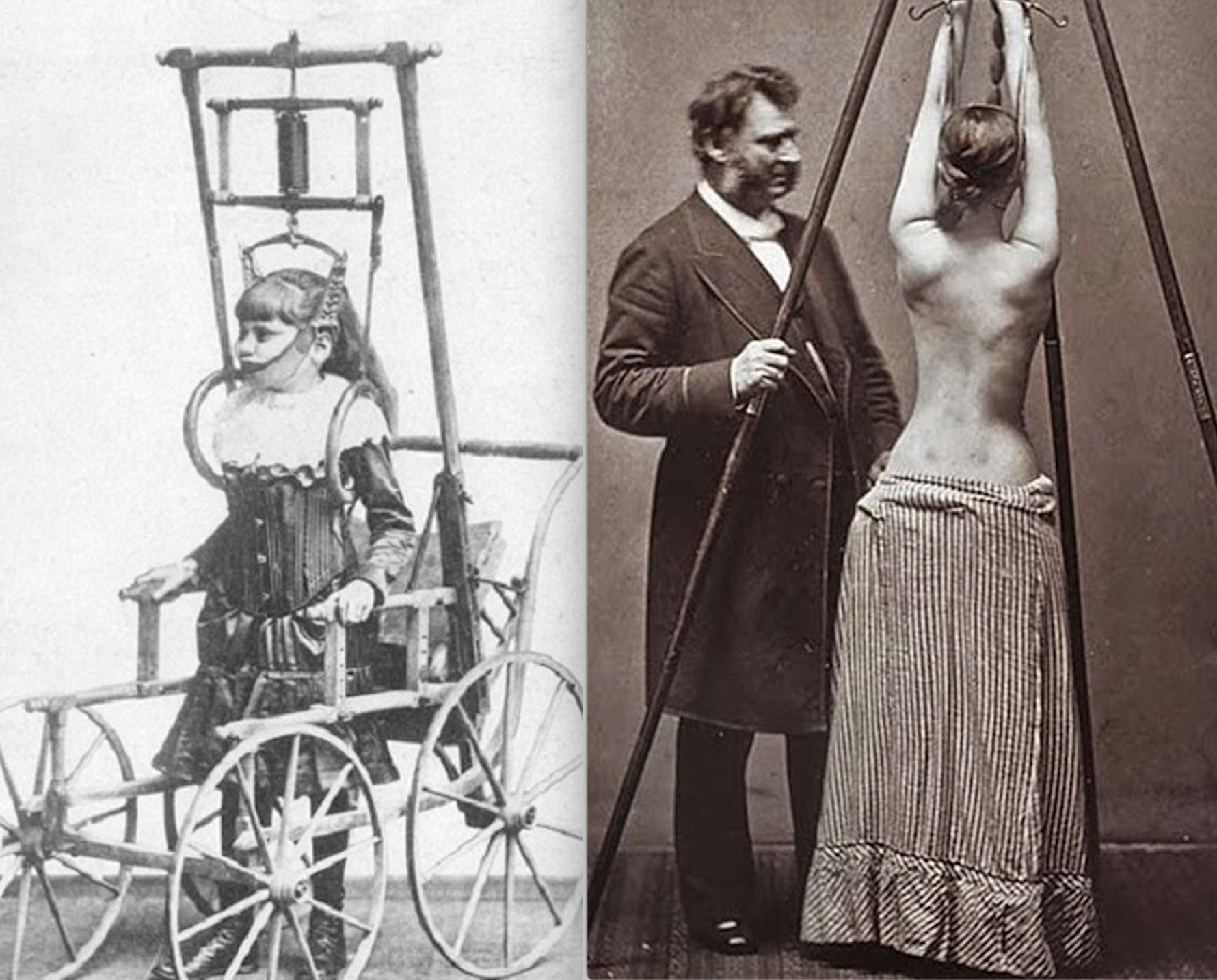

Scoliosis surgery goes as far back as the 1860s, when a French surgeon named Jules Rene Guerin experimented on more than 1,300 patients by severing muscles and tendons in their backs and attempting to realign the spinal column. The results were horrific and led to an infamous lawsuit, one of the first recorded instances of surgeons disputing in court.

The earliest versions of spinal fusion came in the early 1900s, from doctors named Russell Hibbs and Fred Albee. “Those early surgeries were marred by patients being on prolonged bed rest,” said Baron Lonner, a surgeon and professor of orthopedic surgery at Mount Sinai in New York. “Patients would be placed in body casts, and kept in bed for as long as a year in some cases.”

At that point, there were no rods and screws yet to hold the spine correction in place. “Often, the spine didn’t fuse or heal in that stable position,” Lonner said. “So patients would have pain, loss of correction, and subsequent additional operations.”

Then, in the 1950s, came a new standard of care. The Harrington rod was a single rod, with a hook at the top and a hook at the bottom, that held the spine in place for fusion. It was a huge improvement. But usually patients still had to wear a full body cast for months — and over time, they could experience major complications.

“The problem with the Harrington rod was that it didn’t take into account the three-dimensional nature of the spine,” Lonner said.

When you look at a spine from the front or back, it should be straight. But when you look at a spine from the side, it should have a series of curves. The Harrington rod did a poor job of maintaining those natural curves.

People who’ve gotten spinal fusion over the years often have mixed feelings about their experience — particularly the farther back you go.

Eliana Bergman is 33 years old, originally from Florida but currently living in Jordan. When she was 11, an orthopedic doctor told Bergman her scoliosis had gotten so severe that it was life-threatening. Bergman recalled him saying, “If you don’t have surgery, you’re probably going to die. Your rib cage is going to collapse, and your lungs are going to be smushed. You’re not going to be able to breathe.”

By age 12, Bergman had two curves in her back: 74 degrees on top and 54 degrees on the bottom. She got her first Harrington rod surgery in 1999 to correct the top curve. In 2005, she got surgery for her lower back. “So I’m fused basically from top to bottom,” she said.

She’s aware that spinal fusion potentially saved her life. But it also came with complications, like muscle spasms and nerve issues. It didn’t get rid of her daily pain, it just changed it. And the surgeries permanently restricted her motion.

“I’m just like a big piece of metal or wood that’s just very stiff. If I’m bending over forward to, for example, tie my shoes, I literally look like a piece of wood,” Bergman said. “I don’t have a curve, a natural curve to just be able to bend over.”

But in the two decades since Bergman’s surgeries, spinal fusion has seen major upgrades. The metal rod implanted along the spine has gotten more flexible.

“For a child today that gets a spinal fusion, instead of being a life-altering event, I describe it more as a bump in the road,” Cahill said. “It generally does not seem to have any long-lasting detrimental impact on their function throughout the rest of childhood and into adulthood.”

Rather than spending months in the hospital, Cahill said, spinal fusion patients today are typically out of the hospital after three days, back in school after three weeks, and back to most sports after three months.

‘Just the news I needed to hear’

Despite those improvements, back in Parker, Pennsylvania, Beth Pentz was not happy to hear Bailey’s doctor prescribe a spinal fusion. “I actually know a couple people that have had rods, and they tell me they live in pain every day. They also don’t have mobility like they’d like,” she said.

“We left that appointment feeling very, very defeated,” she added. “I went out in the waiting room and just kind of cried and cried, and just didn’t know where to go from there.”

Beth posted an update on Facebook. And that’s when a mom from a scoliosis support group called Curvy Girls contacted her. “She said, ‘I think you need to consider VBT,’ and she explained what it was to me,” Beth said. “It was just the news that I needed to hear at that point. It gave me hope.”

VBT, or vertebral body tethering, is a new surgery that ditches the metal rod and instead threads a rope through screws placed on each vertebra. It was just approved by the FDA in August 2019 — before that, it was still considered experimental.

It is meant for patients who are still growing. A tether that looks like a clothesline holds the long part of the spine in place, so that the short part — the part that curves in — can catch up as it grows. Think of it like taking a tomato plant that’s bending over to one side and tethering it so it straightens out over time.

Just two weeks after the phone call in which Beth learned about VBT, the Pentz family made a six-hour-plus drive. They were going to meet with a pioneer in VBT: Amer Samdani, chief of surgery at Shriners Hospital for Children in Philadelphia.

“I just prayed to God repetitively for the whole ride, ‘Please let her be a candidate for this surgery,’” Beth said.

Pluses and minuses

After talking with Samdani, however, things actually felt less clear to the Pentzes. “He said she’d be very successful for fusion or for VBT, and he listed all the pros and cons of both,” Beth said.

In terms of VBT pros, “the main benefit is that the rope is flexible,” Samdani said. “There’s no doubt that compared to rods VBT patients move dramatically better.” That’s a big plus for gymnast-cheerleader Bailey. VBT patients are typically back to sports within weeks, compared to months for fusion patients.

Tethering is also less invasive — rather than making a huge cut down the back that leaves a big scar, VBT requires just six small incisions, through which the surgeons insert all their equipment, and the tether. And, while a spine can’t be unfused, tethering is reversible. The rope can be released or adjusted.

As for VBT cons, “the biggest drawback is the predictability is not as high as with the fusion,” Samdani said. “If you want to reliably get your spine straight, then fusion’s the better option. With VBT, because it relies on growth remaining in a child, the end result can be hard to predict.”

Meaning, with VBT, there’s a fairly good chance that the patient will need a follow-up surgery. So far, about 20% of Samdani’s patients have needed repeat intervention. Sometimes, the spine overcorrects and starts curving the other way. Sometimes, the rope breaks. There’s always a chance that the tether won’t do the job and the patient will need to get a fusion anyway.

Samdani also does a fair deal of fielding spinal fusion horror stories from the past. “Our first several patients were patients who needed spinal fusion — needed rods in their back — but whose mom or aunt had previously had a spinal fusion and was very unhappy for whatever reason,” he said. “And they had set in their minds that, no matter what, they were not going to let their niece or daughter have fusion surgery.”

“There is this shifting baseline, and we spend a considerable amount of time telling them, listen, spinal fusion has evolved,” Samdani said. “It’s a good operation.”

All that was a lot of information for the Pentzes. “He was very honest about everything, and it just made it hard,” Beth said. “I [thought I] knew what I wanted, but then when he listed all the cons, I guess, I had to take some time to think about it.”

She even tried the old line, “If this was your daughter, what would you do?”

“And no one would answer that question for me,” she said.

Her husband and Bailey’s dad, Josh Pentz, actually left that first appointment in favor of spinal fusion. “When he heard the doctor say ‘One and done,’ he was like, ‘Oh we should do fusion, we’ll never have to worry again,’” Beth said.

Plus, Josh added, it just seemed smart to go with the more established option, the one with more history. It’s “10 years versus 55 years,” he said.

The decision

In the end, the Pentzes chose VBT.

After their initial consultation, Beth dove into the research. The medical professionals might not give her an opinion, but the scoliosis communities she found online had a lot to say.

“I wouldn’t even have come here if it hadn’t been for a mother I met through Curvy Girls,” she said at the hospital. “And we had never spoken on the phone before, just, you know, IM-ing on Facebook.”

Beth talked to families that had done both fusion and VBT, and got more enthusiastic responses from the VBT families. Other Curvy Girls moms told her that if it were their daughter, they’d go with VBT. “It just felt like everyone was directing me that way,” she said.

But the most important factor in the end? Bailey wanted VBT. “I knew I didn’t want the rods because I couldn’t do gymnastics and stuff,” Bailey said.

“This has to be her decision,” Beth said. “It’s her life, ultimately. We are her parents, we need to make sure she’s safe, but you know, this is her life to live.”

However, not everyone makes the same decision. Though VBT holds immense promise, it does lack long-term data — and that concerns some patients.

Erik is 15 years old and lives in Frankfurt, Germany. He didn’t want his last name used because he’s underage. Last fall, he felt torn between fusion and tethering — but after a lot of back and forth, he ended up going for fusion.

“The main point that finally convinced me to get spinal fusion was that the long-term effects of tethering weren’t really known that well,” he said. “I didn’t really want to become a human experiment.”

The first VBT patients only got their tethers 10 years ago. For some spinal fusion patients, problems don’t crop up until two or three decades after surgery.

Amy Tucker Hayden lives in Texas and got a fusion in 1989, when she was 12. She said, after her initial recovery, “I was great. I never thought about it.” Hayden had no pain through all of her 20s and most of her 30s. She traveled the world, did everything she wanted to do (though, she added, she was never super athletic.)

But now? “Now, it’s bad,” Hayden said.

In her 40s, Hayden is experiencing a lot of degeneration. She feels daily pain in her neck and lower back, sometimes down her limbs. It’s a problem that can’t easily be fixed. Instead, she’s learning to live with it.

Doctors say they don’t expect VBT’s long-term prospects to be quite so bad. After all, it’s a much less invasive procedure. But still, it’s uncharted waters.

“What will be interesting is to see how the VBT procedure changes the natural history of long-term outcomes,” said Baron Lonner, from Mount Sinai. “My hope is that VBT patients may do well and do better long term, but that remains to be seen.”

Lonner said there’s also another slice of the health care world that’s waiting for more long-term data before making a lasting decision: insurance companies.

The average cost of a hospital stay for a child with scoliosis is $92,000. So far, insurance coverage for VBT has been variable. No standards have been set. And insurance companies do have the power to make or break a new treatment.

For instance, some years ago, there was a promising new procedure for lower back pain, called total disc replacement. But it ultimately never got off the ground, “because the insurance companies decided collectively that they did not want to support it,” Lonner said. “They were afraid it would just open the floodgates, without long-term outcomes to be offered.”

For this reason, it will be critical to collect good data about VBT outcomes, Lonner said. He hopes that, plus the widespread support VBT has already garnered from patients and their families, will make it “difficult for the insurance companies to say no.”

The Pentzes said cost wasn’t a huge deciding factor for them. Their small town came together to support Bailey’s operation — plus, Shriners takes care of patients regardless of their ability to pay.

What’s next?

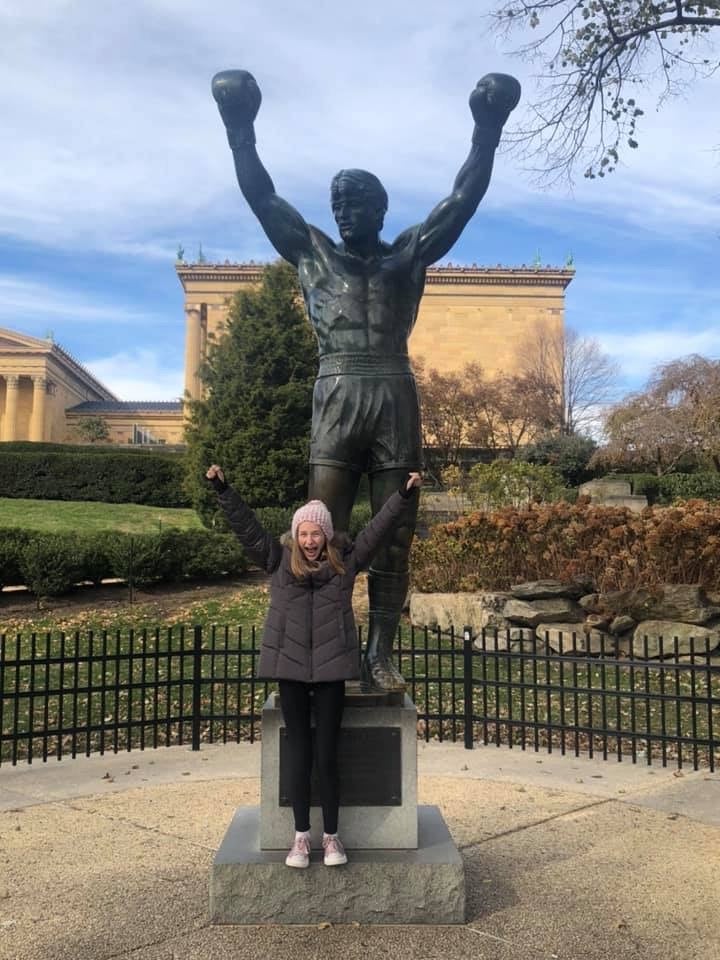

Three days after Bailey’s VBT surgery, Beth Pentz said Bailey had been a champ — she started walking laps around the hospital floor the day after surgery. And already, Beth had noticed some changes. “Her shoulders were very uneven prior to surgery,” she said, “and I feel they’re leveling out to look pretty equal.”

Bailey felt a little different too. “It’s like, I feel it made me taller,” she said. “I don’t know if it actually did, it just feels like it.”

Even dad, who was on the fence, felt the family had made the right decision. “Well, it’s only the first week, but I’m very pleased with it,” Josh said. “She seems to be recovering nicely.”

Meanwhile, medicine continues to evolve. There’s already another scoliosis surgery coming down the pike, called ApiFix. It involves a rod with a ratcheting device that can move as the spine corrects over time. Lonner, at Mount Sinai, said he hopes to start performing that operation before the end of the year.

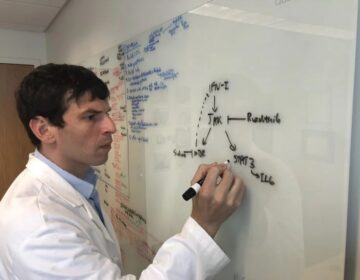

Samdani said the possibilities aren’t even just limited to new surgeries. As scientists gain a better understanding of the causes of scoliosis, solutions in gene therapy or gene editing may be on the horizon. Doctors are already using gene therapy to treat other spinal disorders.

“Perhaps rather than even needing an incision you just have an injection into your discs that are abnormal,” Samdani said. “And then my dream is, one day, you can just take a pill and you’re able to, you know, treat your scoliosis.”

“Obviously, that would put a lot of surgeons out of business, but that’s OK,” he said.

As for whether Bailey will be able to do a back handspring again?

“I would say, I’m hopeful,” Samdani said. “But we’ll have to wait and see.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.