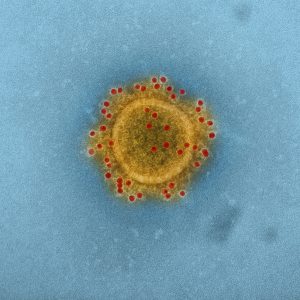

Earlier this month, Chinese media reported that doctors in Yunnan cured a patient from coronavirus with a stem cell transplant. But did they really and do stem cells actually hold promise against the new virus wreaking havoc across the world?

The global pandemic has sent scientists racing to find a cure. There are more than one hundred clinical trials testing potential treatments and vaccines, most of them in China. About a dozen trials are investigating whether mesenchymal stromal/stem cells (MSCs) from cord blood could be used to help alleviate lung damage caused by the infection.

Because of their ability to turn into other cell types, stem cells are usually viewed as a source from which replacement body parts can be grown to treat disease and injury. This indeed was the case in a 2019 report about a man who got cleared of HIV after receiving a blood stem cell transplant to treat his blood cancer. The transplant replaced his immune system—including all the white blood cells invaded by the virus—with those from a healthy HIV-resistant donor.

But the rationale for using stem cells against the new coronavirus is different. The main goal of the transplant is to protect the patient from their own immune system.

COVID-19 can cause severe pneumonia, leading to an overcharged immune response that ends in organ failure. A recent Lancet study found that most patients who died experienced acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), brought on by dangerously high levels of inflammation.

MSCs secrete chemicals that dampen inflammation, at least according to a wealth of data from animal studies. Ongoing human trials are investigating the cells’ potential in alleviating life-threatening graft versus host disease and sepsis, which occur when the body unleashes a violent immune response against unmatched donor tissue and pathogens, respectively. While their efficacy in patients remains to be determined, the cells seem to be safe at least.

It is therefore not surprising that a group in China picked MSCs to battle the virus. The results of one trial have been published so far, grabbing headlines in China and around the world. It is worth noting that the study was published in a journal called Aging and Disease, while the findings were also highlighted in a now withdrawn paid advertisement, in the journal Nature.

It’s a small study in which seven patients received an injection of MSCs while three received placebo. All treated patients began to improve within a couple of days of injection, whereas one placebo patient died, leading authors to conclude that MSC therapy is safe and effective against COVID-19.

The study is, however, too small to make any conclusions about efficacy.

Dr. Bernard Thébaud, a physician and stem cell scientist at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, who investigates whether MSCs can help heal injury in newborns, called the study “opportunistic” and said that it was designed in such a way that no conclusion can be drawn. He also pointed out that it lacks the informed patient consent statement, a legal and ethical requirement for research on human participants. Its absence alone could prompt some experts to disregard the study altogether.

Ian Rogers, a scientist at Sinai Health System’s Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute, who helped establish Canada’s first cord blood bank, Insception Lifebank, had similar concerns. “The main takeaway is that giving patients MSCs did not do any harm and maybe could help, but a much larger study is required,” he wrote in an e-mail.

In addition to the study’s small size, it is also not clear how the patients were chosen. Although all patients were already hospitalized, only one was in critical condition and requiring a ventilator, and with signs of organ failure from inflammation, which MSCs are purported to clear. This patient also had high blood pressure, now a known risk for developing a severe disease. But the study does not mention if the remaining patients also had a preexisting condition, nor why they were treated given that their disease was less severe.

The study’s flaws did not stop the media from reporting on a “cure,” raising false hopes among the public desperate for good news. A video released by an infected Singapore man, asking the authorities to let him be treated with stem cells, is just the latest example of people seeking unproven therapies. Following the flurry of media reports, the International Society for Stem Cell Research, a body dedicated to promoting evidence-based stem cell research, released a statement on their website reminding everyone that so far there’s no approved stem cell treatment for COVID-19.

This does not mean that MSCs don’t have any potential and several companies are gearing to start larger trials. Australian company Mesoblast said that they are planning to test their MSC product Remestemcel-L on COVID-19 patients. This was initially developed for inflammatory lung injury similar to that caused by the virus. The decision was based on encouraging, and as yet unpublished, data from a randomized trial involving 60 patients. Other companies are joining the race: Celltex, Athersys and Lattice Biologics have all announced human trials.

Even if stem cells are shown to cure COVID-19, the question remains whether they work better than other candidates. One of them is Gilead Sciences’ remdesivir, a general antiviral medication whose trial results are expected to be reported next month. There is so much demand for this product, that the company has temporarily suspended access except for certain patient groups.

Despite the great uncertainty brought on by the new coronavirus, one thing’s for sure: the science is moving very quickly. Hopefully in the not too distant future, we’ll have a range of options: vaccines to protect us from getting infected, antivirals for those who forgot their jabs and perhaps even cell therapy to treat those who need it most.

Jovana Drinjakovic

Latest posts by Jovana Drinjakovic (see all)

- Canadian immunotherapy holds promise for patients with brain cancer - September 9, 2020

- Could stem cells be enlisted to battle COVID-19? - March 26, 2020

- Study reveals large differences at the molecular level between stem cells grown on different biomaterials - April 18, 2019

Comments