The disproportionate number of indigenous children caught in Canada’s child welfare system is a “humanitarian crisis” that echoes the horrors of a residential school system that saw 150,000 Aboriginal children forcibly removed from their homes, the Canadian minister responsible for indigenous services has said.

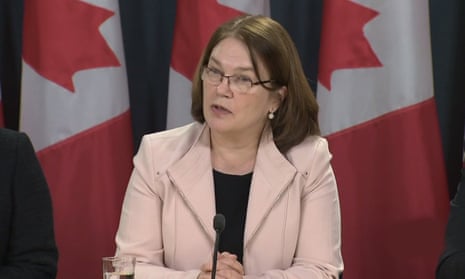

Describing the issue as one of her top priorities, Jane Philpott noted this week that Canada removes indigenous children from their families at a rate that ranks among the highest in the developed world.

“We are facing a humanitarian crisis in this country where indigenous children are vastly, disproportionately overrepresented in the child welfare system,” Philpott told the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

She pointed to the province of Manitoba, where 10,000 of the 11,000 children in care are indigenous. “This is very much reminiscent of residential school systems where children are being scooped up from their homes, taken away from their families and we will pay the price for this for generations to come.”

In 2016, there were 4,300 indigenous children under the age of four in foster care across Canada, according to government statistics. While 7% of children across Canada are Aboriginal, they account for nearly half of all the foster children in the country.

Philpott pointed to the enduring effects of residential schools as well as high rates of poverty to explain the figures. The issue also stems from “bad government policies” of the past, she added.

“We see that there’s discrimination against indigenous kids, where they are apprehended from their homes for reasons like poverty, or lack of adequate housing or food,” she said. “Well, kids need to be with their families and in their communities and culture, so we should be addressing the housing issue or the adequate food issue, not taking kids away from their families.”

While First Nations housing and food security on reserves fall under federal jurisdiction, Philpott said she had called an emergency meeting with her provincial and territorial counterparts – who are primarily responsible for administering child welfare programs – and indigenous leaders to address the issue. The meeting is expected to take place early next year.

Philpott’s comments came as indigenous leaders gathered on Parliament Hill for a day of action aimed at pushing the federal government to comply with a 2016 ruling by the Canadian human rights tribunal that found the federal government was discriminating against indigenous children by underfunding health and welfare on reserve.

“Our message today is simple,” Kevin Hart of the Assembly of First Nations told reporters. “Stop taking our children from us, honour the tribunal ruling, and work with us to give our children hope and opportunity.”

A spokesperson for Philpott’s office noted that Ottawa made available C$200m in funding last year to implement the tribunal’s ruling and has committed another C$256m in funding this year. In a statement, her office added: “We recognize there is more work to do, and we remain absolutely committed to putting an end to the colonial policies of previous governments and ensuring the right supports are in place in order to bring justice for Indigenous children.”

Still, nearly two years on – and despite three non-compliance orders issued by the tribunal to the current Liberal government – Ottawa has yet to fully comply with the ruling, said Cindy Blackstock, the executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society.

Instead Aboriginal children living on reserve continue to receive less than others in the country. “They get less funding for education, less funding for healthcare, less funding for basics like water and sanitation and less funding for child welfare to recover from the multigenerational impacts of residential schools,” she said.

The result has left some First Nation communities struggling with inadequate, overcrowded housing and water that is not safe to drink. Others grapple with a shortage of mental health services, amid youth suicide rates that are 10 times higher for First Nations males and 21 times higher for females as compared to their non-indigenous counterparts.

“Canada cannot become comfortable or acquiesce to the idea that we are a nation that relies on racial discrimination against children as a fiscal restraint measure,” said Blackstock.

She drew a direct line between the chronic underfunding and the staggering numbers of Aboriginal children being taken away from their families, culture and communities. “There are more First Nations kids in child welfare today than at the height of residential schools,” she said. “Ottawa is not doing everything they can to make sure that this isn’t another generation of First Nations kids that don’t have to recover from their childhood.”